Corpus Juris Civilis

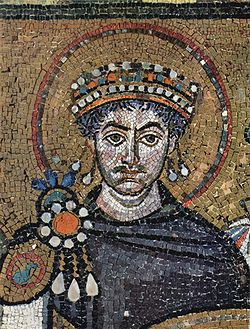

The Corpus Juris (or Iuris) Civilis ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name[1] for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Eastern Roman Emperor. It is also referred to as the Code of Justinian.

This code compiled, in Latin, all of the existing imperial constitutiones (imperial pronouncements having the force of law), back to the time of Hadrian. It used both the Codex Theodosianus and the fourth-century collections embodied in the Codex Gregorianus and Codex Hermogenianus, which provided the model for division into books that were divided into titles. These codices had developed authoritative standing.[2]

Justinian gave orders to collect legal materials of various kinds into several new codes, spurred on by the revival of interest in the study of Roman law in the Middle Ages. This revived Roman law, in turn, became the foundation of law in all civil law jurisdictions. The provisions of the Corpus Juris Civilis also influenced the Canon Law of the church since it was said that ecclesia vivit lege romana — the church lives under Roman law.[3]

The work was directed by Tribonian, an official in Justinian's court, and distributed in three parts: Digesta (or "Pandectae"), Institutiones, and the Codex Justinianus. A fourth part, the Novels (or "Novellae Constitutiones"), was added later.

The Corpus Juris Civilis was composed and distributed in the Latin language, which was still the official language of the government of the Empire in 529–534 C.E., whereas the prevalent language of merchants, farmers, seamen, and other citizens was Greek. By the early 7th century, the official government language segued into the Greek under the lengthy reign of Heraclius (610–641).

Contents |

Contents

Codex Justinianus

The Codex Justinianus (Code of Justinian, Justinian's Code) was the first part to be completed, on April 7, 529. It collects the constitutiones of the Roman Emperors. The earliest statute preserved in the code was enacted by Emperor Hadrian; the latest came from Justinian himself. The compilers of the or also removed repetitive or iniquitous laws, in order to “afford all men the ready assistance of true meaning.”

Legislation about religion

Numerous provisions serve to secure the status of Orthodox Christianity as the state religion of the empire, uniting Church and state, and making anyone who was not connected to the Christian church a non-citizen.

- Laws against heresy

The very first law in the Codex requires all persons under the jurisdiction of the Empire to hold the holy Orthodox (Christian) faith. This was primarily aimed against heresies such as Arianism. This text later became the springboard for discussions of international law, especially the question of just what persons are under the jurisdiction of a given state or legal system.

- Laws against paganism

Other laws, while not aimed at pagan belief as such, forbid particular pagan practices. For example, it is provided that all persons present at a pagan sacrifice may be indicted as if for murder.

Digesta

The Digesta or Pandectae consist of a collection of legal writings mostly dating back to the second and third centuries. Fragments were taken out of various legal treatises and opinions and inserted in the Digest. In their original context, the statements of the law contained in these fragments were just private opinions of legal scholars. The Digest, however, was given the force of law, like the other parts of the Corpus Juris. This section of the Corpus Juris was completed in 533.

Institutiones

As the Digest neared completion, Tribonian and two professors, Theophilus and Dorotheus, made a students' textbook, called the Institutiones or 'Elements'. As there were four elements, the manual consists of four books. The Institutiones are largely based on the Institutiones of Gaius. Two thirds of the Institutiones of Justinian consists of literal quotes from Gaius. The new Institutiones were used as a manual for jurists in training since 21 November 533 and were given the authority of law on 30 December 533 along with the Digest.

Novellae

The Novellae consisted of new laws that were passed after 534. They were later re-worked into the Syntagma, a practical lawyer's edition, by Athanasios of Emesa during the years 572–77.

Continuation in the East

Byzantine Empire (East Roman Empire) was the successor of the Roman Empire and continued to practice Roman Law as collected in the Corpus Juris Civilis. This law was modified to be adequate for the new social relationships in the Middle ages. Thus the Byzantine law was created. New legal codes, based on Corpus Juris Civilis, were enacted. The most known are: Ecloga[4] (740) - enacted by emperor Leo the Isaurian, Proheiron[5] (c. 879) - enacted by emperor Basil the Macedonian and Basilika (late 9th century) - started by Basil the Macedonian and finished by his son Leo the Wise. The last one was complete adaptation of Justinian's codification. At 60 volumes it proved to be difficult for judges and lawyers to use. There was need for a short and handy version. It was finally made by Constantine Harmenopoulos, a judge from Thesaloniki, in 1345. He made a short version of Basilika in six books, called Hexabiblos. Serbian state, law and culture was built on the foundations of Rome and Byzantium. Therefore, the most important serbian legal codes: Zakonopravilo (1219) and Dušan's Code (1349 and 1354), transplanted Roman-Byzantine Law included in Corpus Juris Civilis, Prohiron and Basilika. These Serbian codes were practised until Serbian Despotate failed under Turkish Ottoman Empire in 1459. After the liberation from the Turks in the Serbian Revolution, Serbs remained to practise Roman Law by enacting Serbian civil code in 1844. It was a short version of Austrian civil code (called Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch), which was made on the basis of Corpus Juris Civilis.

Recovery in the West

Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis was distributed in the West[6] but was lost sight of; it was scarcely needed in the comparatively primitive conditions that followed the loss of the Exarchate of Ravenna by the Byzantine empire in 8th century. The only western province where the Justinianic code was effectively introduced was Italy, following its recovery by Byzantine armies (Pragmatic Sanction of 554), but a continuous tradition of Roman law in medieval Italy has not been proven.[7] Historians disagree on the precise way it was recovered in Northern Italy about 1070: perhaps it was waiting unneeded and unnoticed in a library until the legal studies that were undertaken on behalf of papal authority that was central to the Gregorian Reform of Pope Gregory VII led to its accidental rediscovery. Aside from the Littera Florentina, a 6th-century codex of the Pandects that was preserved at Pisa, apparently without ever being publicly consulted, (and removed to Florence after Florence conquered Pisa in 1406), there may have been other manuscript sources for the text that began to be taught at Bologna, by Pepo and then by Irnerius. The latter's technique was to read a passage aloud, which permitted his students to copy it, then to deliver an excursus explaining and illuminating Justinian's text, in the form of glosses. Irnerius's pupils, the so-called Four Doctors of Bologna, were among the first of the "glossators" who established the curriculum of Roman law. The tradition was carried on by French lawyers, known as the Ultramontani, in the 13th century.

The merchant classes of Italian communes required law with a concept of equity and which covered situations inherent in urban life better than the primitive Germanic oral traditions. The provenance of the Code appealed to scholars who saw in the Holy Roman Empire a revival of venerable precedents from the classical heritage. The new class of lawyers staffed the bureaucracies that were beginning to be required by the princes of Europe. The University of Bologna, where Justinian's Code was first taught, remained the dominant centre for the study of law through the High Middle Ages.

It is interesting that the name of Justinian's codification ("Corpus Juris Civilis") was adopted in 16th century, when Dionysius Gothofredus printed the codification in 1583, with the title Corpus Iuris Civilis.

See also

- Byzantine law

- List of Roman laws

- Basilika

- Zakonopravilo

- Dušan's Code

- Code of Hammurabi

- Henry de Bracton

- Frederick Barbarossa

External links

- Corpus Juris Civilis (Complete translation as "The Civil Law" by S.P. Scott, 1932)

- The Roman Law Library, incl. Corpus Iuris Civilis (Latin & Translations)

- Annotated Justinian Code (English translation by Fred H. Blume, completed in 1943)

- The Novels (English translation by Fred H. Blume)

- Selected Laws of Justinian (Internet Medieval Sourcebook)

- Mommsen's edition

Footnotes

- ↑ The name "Corpus Juris Civilis" occurs for the first time in 1583 as the title of a complete edition of the Justinianic code by Dionysius Godofredus. (Kunkel, W. An Introduction to Roman Legal and Constitutional History. Oxford 1966 (translated into English by J.M. Kelly), p. 157, n. 2)

- ↑ George Long, in William Smith, ed., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, (London: Murray) 1875 (On-line text).

- ↑ Cf. Lex Ripuaria, tit. 58, c. 1: "Episcopus archidiaconum jubeat, ut ei tabulas secundum legem romanam, qua ecclesia vivit, scribere faciat". ([1])

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178179/Ecloga

- ↑ http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/img/doi/0584-9888/2004/0584-98880441099S.pdf

- ↑ As the Littera Florentina, a copy recovered in Pisa, demonstrates.

- ↑ Kunkel, W. (translated by J.M. Kelly) An Introduction to Roman Legal and Constitutional History. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1966; 168-69

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||